American dueling took root as early as the first colonial settlers in the 16th century and was popular throughout most of the 19th century. During these times, nothing was more valuable to a man than his honor—how he was viewed by the public. In the 19th century, politicians, lawyers, and newspaper editors were the most common participants in duels. As you’ll see in my post about gentlemen’s code of conduct, or etiquette, gentlemen went to great lengths to avoid offending each other.

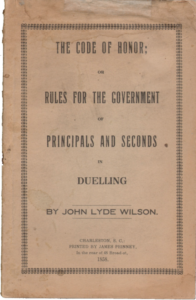

Just as there were rules for being a gentleman, there were rules for dueling combat. Until 1838, most duels operated under the twenty-six rules of the Irish Code Duello, but in 1838, then-former South Carolina Governor John Lyde Wilson published The Code of Honor, a 22-page booklet that included rules for the principals (duelists), the Seconds (friends/managers), and with guidelines for the “field of honor” and weapons, as well as the proper way to exchange related notes. The booklet was small enough to carry with one’s dueling pistols.

The booklet begins with an interesting note to the reader that explains the motives behind its creation. It also includes this justification for dueling: “If an oppressed nation has a right to appeal to arms in defence of its liberty and the happiness of its people, there can be no argument used in support of such appeal, which will not apply with equal force to individuals.” Sounds to me like a well, if the nation can do it, so can we kind of logic. tsk, tsk!

When a gentleman felt offended, he sent a formal note to the offender by way of his friend (or second), asking for a retraction of the menacing action or words. Any response was exchanged the same way—via the offender’s friend (second). When an offended man didn’t receive “satisfaction” by way of retraction and apology, he could seek it by challenging his offender to a duel on the “field of honor.” If both parties were gentlemen, the challenged was rather stuck with accepting.

To decline a challenge was risky and ill-advised. As The Code of Honor explains, a man who refused a challenge could be “posted.” In other words, a description of his bad behavior would be printed and posted in a public place for all to see, along with notice that he had refused the challenge. Anyone concerned with his reputation would not decline.

Once the duel challenge was accepted, each man (now a principal) announced his official “second.” The seconds’ job was to be an intermediary—to prevent the duel and restore all honor by negotiating a compromise. If the seconds failed to prevent the duel, their job was then to manage all details of the fight to ensure fairness.

First page of Lincon’s handwritten duel instructions and terms. Note the first term, weapons, at bottom.

An interesting analysis of duels (including the Hamilton-Burr affair), from a 2004 perspective, can be found in Alison LaCroix’s article titled “To Gain the Whole World and Lose His Own Soul: Nineteenth-Century American Dueling as Public Law and Private Code,” published by The University of Chicago Law School’s Unbound.

Add photos here.