The back matter for King of the Tightrope is fabulously designed by the smart folks at Peachtree Publishing, but there’s more to the story than fit the limited pages available. In the Author’s Note and Afterword below, you’ll learn a bit more about the uncovered history of Jean Francois Gravelet, The Great Blondin. Watch for other posts about the specific STEAM connections.

Author’s Note:

One night in 2010, I was making dinner while a television special about the history of Niagara Falls kept me company. I remained at my task until the program narrator mentioned that a man named Jean-François Gravelet, aka The Great Blondin, performed on a tightrope over the Niagara River in 1859. The Blondin segment lasted one or two minutes—long enough to grab me. I had to learn more.

My pursuit of Blondin’s story, especially his step-by-step process at Niagara, proved challenging, as historical research usually is. I bought manila ropes so that I could experience them under my feet. To get into the head of a tightrope walker, I read and watched interviews with modern funambulists like Philippe Petit (the man who tightroped between the World Trade Centers) and The Flying Wallendas. I dug into the past through U.S. and Canadian newspaper articles and eye-witness accounts of Blondin’s performances. Unfortunately, those sources contained conflicting, misleading, and missing details. When I located the first biography about Blondin, published in 1862, I thought I had struck gold.

This biography became the central source from which all later biographical information about Blondin was drawn. Unfortunately, as I later discovered, the biography was partly fictionalized, and those fictional elements were perpetuated for almost 160 years.

To distill the binders full of information that I had collected down to the most credible sources about how Blondin engineered his rope, and to fill in the missing pieces, I first turned to my eldest son Justin, who had recently earned an engineering degree. Documented reports and photographs in hand, we brainstormed possibilities and logical assumptions, while he sketched and employed physics calculations that went over my head. Though Blondin relied mostly on his intuitive knowledge of rope and rigging to determine how he would stretch his rope across the Niagara Gorge, to deconstruct the process, a century and a half later, required an engineer’s thought process. Actually, it required the logic of two engineers.

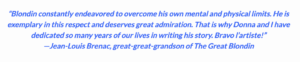

I was fortunate to connect with Blondin’s Great-Great-Grandson in France. As luck would have it, Jean-Louis is a fluent English speaker, a brilliant retired engineer, AND the author of a well-researched, not-yet-published French biography about Blondin, which he kindly shared with me. Eureka! With his help and expertise, the missing pieces of Blondin’s life and his Niagara rope process slowly fell into place. Jean-Louis’ input, support, and encouragement made this book infinitely better. Now, I am pleased to help him correct the historical record about his ancestor.

I was fortunate to connect with Blondin’s Great-Great-Grandson in France. As luck would have it, Jean-Louis is a fluent English speaker, a brilliant retired engineer, AND the author of a well-researched, not-yet-published French biography about Blondin, which he kindly shared with me. Eureka! With his help and expertise, the missing pieces of Blondin’s life and his Niagara rope process slowly fell into place. Jean-Louis’ input, support, and encouragement made this book infinitely better. Now, I am pleased to help him correct the historical record about his ancestor.

Process aside, what’s most notable about The Great Blondin is what his remarkable feats teach us about imagination, determination, and the will to succeed.

Afterword:

Despite the perpetuated inaccuracies about Jean-François Gravelet, he was born into an acrobatic family in 1824. It is said that he made his first public appearance at fifteen months old when his father pushed him in a wheelbarrow on a tightrope at the Coronation of France’s Charles, X. At the age of four, Jean-François climbed a slant rope toward his older sister who was experiencing troubles on the rope. The public took notice. At age eight, Jean-François performed for the King of Sardinia, and continued to perform with his family throughout France and beyond.

To ensure safety during any rope-walking endeavor, Jean-François learned how to properly rig and attach his own ropes, and he learned how to choose the size of ropes that would hold up at different heights, distances, and conditions. Though his older sister Pauline and younger brother Louis were also performers and rope walkers, Jean-François was destined to become the most famous rope-walker in the world. An interview with Blondin, published thirty years after the Niagara feats, claimed that Blondin had stood on his head so often on a rope that a ridge had formed in his skull.

As a young man, Jean-François married a French acrobat named Rosalie with whom he had four children, though two of the children did not survive.

In 1851, he said goodbye to his family and boarded the Germania to sail across the Atlantic for a two-year American performance tour with the Gabriel Ravel troupe. Either because the name Gravelet sounded too similar to Ravel, or because the men worried that American audiences would not be able to pronounce the name Gravelet, blonde-haired, blue-eyed Jean-François took the name Blondin—The Great Blondin. He could not have anticipated that his two-year tour would turn into ten years, beginning with Niblo’s Garden in New York. Sadly, Blondin never saw his French family again.

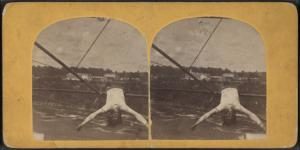

Blondin, remarkably strong at only 5’6” tall and about 145 pounds, performed on his Niagara rope at least seventeen times during the summers of 1859 and 1860. In 1860, he moved his rope to the opposite side of the Railroad Suspension Bridge, directly over the deadly whirlpool rapids. Both years, besides acrobatics on the rope, he performed increasingly difficult and dangerous stunts, including carrying a cookstove and preparing an omelette, carrying a table and chair to enjoy a glass of bubbly, and carrying his manager on his back. He walked across the Niagara rope on stilts. He balanced on a chair (that plunged into the river), he performed at night with Bengal lights attached to his pole (they fell into the river, forcing him to walk in darkness above the rapids), and he walked with his feet in peach baskets and his arms and legs in chains. In September of 1860, the Prince of Wales watched in awe but refused Blondin’s offer to carry him across the gorge on his back.

Amateur rope walkers tried to compete with Blondin for attention and money, but none compared to the elegance, strength, and expertise of The Great Blondin.

While in the United States, Blondin married a young performer named Charlotte Sophia Lawrence in Boston, with whom he had five children. In 1861, shortly after the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter, which sparked the Civil War, Blondin and his family boarded The Bremen and sailed to England in time for his contracted performances at London’s Crystal Palace, which is where his use of a bicycle on the rope was first documented. Blondin purchased a home in Ealing, England, and named it Niagara Villa.

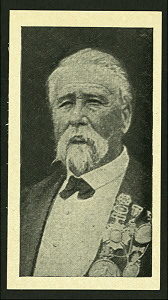

Blondin performed on the tightrope for the rest of his life, eventually claiming that performing on a bicycle on the rope was his most dangerous feat, while performing on a balanced chair was the most difficult. He continued to challenge himself with feats of ever-increasing danger, like performing between the masts of a sailing ship, pushing a live lion, or his children, and sometimes trundling fireworks (which once exploded while he was on the rope). Though he chose a lifetime of dangerous stunts as a career, Jean Francois never allowed a safety net, saying “the danger is half the fun.” For his extraordinary career, he was presented with multiple gold medals and awards, including a Spanish knighthood.

I can’t wait to read this book to my Grandson. I grew up in Buffalo and I’ve been to the Falls a few times, and I can’t imagine doing what he did! Or even thinking about doing it!